A Brief History Of Asanas In Hatha Yoga

Let’s talk about the history and evolution of asanas in hatha yoga!

Modern Yoga is synonym with asana, or postural practice: it is very common for the vast majority of teachers to base their classes on posture, even when offering meditation as part of their classes.

This makes it extremely easy for everybody to practice: just pick up a book, a video, or even an app on your phone, and you are good to go! No physical teacher needed!

There is a lot of talk about mindfulness, especially when it comes to movement. The implication is that meditation naturally arises during physical practice. It comes with being grounded, present, and achieving the perfect pose as fast as possible.

It may come as a surprise then to know that when Swami Vivekananda came to the West to teach yoga in the late 1800s, he was against the practice of asanas altogether! He claimed postural practice would lead the practitioner to cling to their own body even more, thus holding them back from achieving significant spiritual growth.

When Vivekananda introduced his vision of yoga in the West, there was also widespread prejudice around Indian yogins (especially haṭha yoga practitioners), shared by both Europeans and locals. Yogins and ascetics were the only ones who were seen practicing postures in public settings, and they were seen as ill-tempered mendicants.

According to some, modern yoga has been filtered so much that the term ‘yoga’ may no longer be appropriate at all.

So how is there so much focus on asanas in hatha yoga today?

Hatha yoga used to be considered a lesser practice

The term hatha yoga can be understood in two ways:

- “yoga of force“, due to the effort required to practice it, specifically referring to techniques such as prāṇāyāma (breath control) which are strenuous and may even cause pain;

- “the union of the sun (ha) and the moon (ṭha) in the body“.

Additionally, the term hatha yoga can be found in Buddhist tantras, but was understood as preliminary practice to meditation.

This same pattern can be found in later Vedanta and Yoga literature, where hatha yoga was presented in conjunction and with rivalry with raja yoga. Some texts claim that raja yoga is superior because it is effortless yet fruitful, while hatha yoga is an unnecessary effort. At other times, hatha yoga is understood as a simplified practice for second-rate students.

A few centuries later, the Haṭayogapradīpikā joined hatha and raja yoga into a complete system, still under the name of haṭha yoga, asserting that they are dependent on each other. This is the first instance where some spotlight is given to asana practice: previous texts only generally recommended firm and comfortable sitting postures for the purpose of the other ancillary parts of yoga. Even the Bhagavadgita, one of the most famous texts on yoga, skims over postural practice.

Traditional texts skim over the practice of asanas in hatha yoga

First of all it should be mentioned that not all texts that are considered to be part of the hatha yoga corpus openly refer to hatha, however all the techniques they present were later incorporated into the Haṭayogapradīpikā. Such techniques regarded:

- pranayama

- ten mudras (seals)

- diet

- the stages of yoga

- samadhi

The satkarmas (or cleansing practices) and asanas other than seated meditation postures were also first brought up in the Haṭayogapradīpikā. However, the text still only teaches fifteen asanas, only six of which are non-seated.

Some texts define asanas as a comfortable posture “in which continuous reflection on brahman is easily possible.” (Aparoksanubhuti, v 112)

Other texts explain that the goal of asanas is fitness, health, lightness of the body, yet they only hold a preparatory and subordinate place in the pursuit of liberation from the cycle of rebirth.

There is no final agreement on how many asanas there are. Some texts claim 180, others claim it’s as many as species of living beings, others claim it’s 84 asanas as taught by Shiva. Older texts claim that of the 84 asanas, only a small number is actually important.

Only two texts talk extensively of all 84 asanas, and yet they accompany the performance of such postures with practices of meditation and pranayama. This highlights that even at this point, asanas in hatha yoga were not the only focus but rather a basic tool for a higher technique.

Vivekananda was against asana practice

As previously mentioned, the late 1800s saw a revival of yoga, especially due to the teachings of Vivekananda. However, asanas and other hatha yoga techniques were seen as unsuitable or distasteful by Vivekananda and many of his followers.

Postural practice was associated with unlikeable yogins, seen as street performers and symbols of all that was wrong in certain branches of the Hindu religion, and therefore asanas came to be associated with backwardness and superstition. Not to mention that contortionism was already a popular form of entertainment in Europe, meaning that Westerners would have further misunderstood the practice.

But if asana practice was not a feature of the yoga exported by individuals such as Vivekananda, how did it gain so much audience?

During the first half of the 20th century, the world gain interest in physical culture, and everybody wanted to improve their body. It was common belief that people had created an imbalance by focusing too much on intellect, disregarding spirituality and physicality. Thus, people were looking for wholeness.

Yoga became popular as a comprehensive fitness regime

Physical culturists had started experimenting with different techniques, until they established themselves as contemporary expressions of the hatha yoga tradition in the 1920s. Yoga had then become a comprehensive fitness regimen for physical, mental and spiritual growth.

Understandably, the postural side of yoga was the most appealing to physical culturalists, and physical fitness became the ultimate goal of the practice. A century later, as the craze for physical culture has become less prevalent, postural yoga is still just as prominent.

Yoga classes are available to everyone, from the gym to the work places, in a variety of settings and added props. Modern yoga keeps being reinvented, but the only thing that never changes is the focus on the body.

Quoting Singleton’s book Yoga Body,

“the locus of yoga is no longer at the centre of an invisible ground of being, hidden from the gaze of all but the elite initiate or the mystic […] In the yoga body – sold back to a million consumer-practitioners as an irresistible commodity of the holistic, perfectible self – surface and anatomical structure promise ineffable depth and the dream of incarnate transcendence.” (pg 174)

Sources

- Birch, J. 2011. ‘Meaning of Haṭha in Early Haṭhayoga.‘ Journal of the American Oriental Society. 131.4: 527-54

- Bühnemann, G. 2007. Eight-Four Āsanas in Yoga: A Survey of Traditions, With Ilustrations. New Delhi: DK Printworld.

- Larson, G.J. 2012. ‘Patanjali Yoga in Practice’, in White, D.G. (ed.), Yoga in Practice. Princeton Readings in Religions. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Mallinson, James. ‘Yoga: Haṭha Yoga“, in: Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism Online. Edited by: Knut A Jacobsen, Helene Basu, Angelika Malinar, Vasudha Narayanan.

- White, D.G. 2012. ‘Yoga: Brief History of an Idea’ in White D.G. (ed.), Yoga in Practice. Princeton Readings in Religions. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

If you found my work useful or entertaining and want to say thanks, you can always buy me a cup of tea!

Photo by Shashi Ch on Unsplash

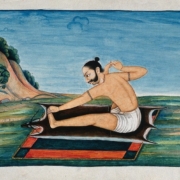

Photo by Shashi Ch on Unsplash Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) terms and conditions https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 Credit: An Indian person of high rank in a yogic posture (the bow pose, or dhanurāsana). Gouache painting by an Indian painter. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) terms and conditions https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 Credit: An Indian person of high rank in a yogic posture (the bow pose, or dhanurāsana). Gouache painting by an Indian painter. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)